Can I-70’s Mountain Corridor Ever Be Fixed? Download PDF

Can I-70’s Mountain Corridor Ever Be Fixed? Download PDF

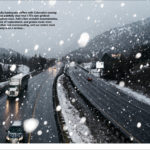

With CDOT’s dreadfully inadequate coffers and Colorado’s soaring population, our state’s most critical east-to-west highway is on a serious collision course.

Shailen Bhatt is hungry. The executive director of the Colorado Department of Transportation is at the wheel of a white Dodge Durango SUV—an official CDOT vehicle, retrofitted with flashing amber emergency lights—when he exits Interstate 70 in Idaho Springs, swoops into a McDonald’s drive-thru, and orders an Egg McMuffin. I’m sitting in the passenger seat. “Do you want anything?” he asks. Bhatt clean-shaves his scalp and is a snappy dresser—he’s wearing a pinstripe oxford, a linen sport jacket, blue jeans, and square-toe leather loafers. At 41, Bhatt is the youngest (and undeniably the most fashionable) director to lead the transportation agency. He is also the kind of man who listens to his wife.

In fall 2014, then CDOT executive director Don Hunt was speaking with Bhatt, who was the secretary of Delaware’s department of transportation. “Don and I were colleagues. We hit it off, and he asked me if I wanted his job,” Bhatt says. “I wasn’t sure. I was like, ‘Been there, done that.’ But my wife always said she wanted to live in Colorado, so I came out and talked to the governor.”

John Hickenlooper was impressed. Bhatt had helped dig Delaware’s transportation department out of deep debt. He had also proven to be resourceful, having dealt with two major hurricanes that severely damaged roadways across his state. It was a first-rate curriculum vitae. But Delaware’s problems weren’t Colorado’s problems. In the Centennial State, Bhatt would be facing a far more difficult challenge: a booming population that has overwhelmed aging highways in a state where voters have repeatedly opposed taxes to fund transportation infrastructure.

Although almost all of the state’s major roads need attention, the traffic-choked I-70 mountain corridor is one of the most urgent problems. The interstate is the principle artery to Colorado’s high-elevation recreation areas (specifically Clear Creek, Eagle, Garfield, Grand, and Summit counties), which not only slake Coloradans’ thirst for playing outside but also generated over 12 percent of the state’s $19.1 billion in direct travel spending in 2015. And therein lies the issue: CDOT estimates that westbound I-70 travel times will triple by 2035; eastbound drivers should expect their commutes to quadruple. (Unless the roadway is expanded—adding both extra lanes and extensive mass transit—the roughly 80-mile drive from Denver to Copper Mountain, for instance, could take four hours one way on a typical winter weekend.) By any measure, an increasingly inefficient I-70 will be catastrophic, robbing Coloradans of their access to the Rockies and costing the state about $839 million annually in 2005 dollars, according to a study done that year by the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce and the Metro Denver Economic Development Corporation.

If that weren’t enough, consider this: There is no major construction currently under way on the mountain corridor, and no new projects are scheduled to break ground in at least the next half-decade. A little more than two years into a job he wasn’t sure he wanted, Bhatt is now keenly aware that this is not a “been there, done that” situation. In fact, it’s pretty likely that no one has ever been in a predicament quite like this one.

In August, I asked Bhatt to take me on a road trip through the mountain corridor so he could show me the effort it takes to both maintain and modernize what is perhaps the most geographically extreme and weather-racked section of interstate in the nation. Rather than covering the entire 144-mile route from C-470 to Glenwood Springs, we confine our outing to an infamously gridlocked stretch—from Morrison to the Eisenhower-Edwin C. Johnson Memorial Tunnel. In the summer, when the worst traffic occurs, weekend backups begin midmorning on Friday and rarely relent until late Sunday evening. The timetable is similar in the winter but is often exacerbated when snowstorms trigger pileups that close the interstate and strand motorists for hours.

About 15 minutes before our stop in Idaho Springs, while driving west, Bhatt pulls into a turnout midway down Floyd Hill. The grade is treacherous, especially for truckers, some of whom drive too fast on snowy roads, lose control, and then jackknife their rigs. “This is wreck central right here,” Bhatt says. But mangled tractor trailers aren’t the area’s only problem. Bhatt gestures toward a wooded slope looming 800 feet above I-70’s eastbound lanes and informs me the entire hillside is creeping toward the roadway, like an advancing glacier. “They call that a moving slide,” he explains. “Before we do anything, we have to stabilize that.” Next he points to the valley below, where an overpass on the interstate crosses Clear Creek. “That bridge is in terrible shape; it’s the second worst in our state.” The price tag to repair both the unstable mountainside and the span over the creek: approximately $500 million. A few miles later, Bhatt directs my attention to several rock slabs that frequently drop boulders onto the roadway—another multimillion-dollar headache.

Bhatt and Hickenlooper, along with the 12 million or so drivers who use the mountain corridor every year, certainly recognize that I-70 no longer functions in its current form during peak travel times. But before it tackles any major upgrades, CDOT must first deal with these more pressing fixes. “You don’t build an addition onto your house—no matter how big your family is—if your furnace is out and your roof is leaking,” Bhatt says. Only after the immediate threats are addressed would it make sense to expand the mountain corridor to three lanes in both directions, a project estimated to cost about $2 billion. Even if Bhatt could rustle up that much cash, a considerable bottleneck would remain: the Eisenhower Tunnel. Until a third shaft is added—which would cost between $1.2 billion and $2 billion—more lanes elsewhere won’t do much good because vehicles would have to squeeze into the existing two-lane tunnel—a tricky uphill merge certain to cause lengthy backups. (This is already evidenced by the bumper-to-bumper crawl that occurs every weekend on the three-lane eastbound climb from Silverthorne to the tunnel.)

For a bit of context, CDOT’s total annual budget is $1.4 billion, an amount that’s hardly enough to cover basic road upkeep, snow plowing, and employee paychecks. The department barely has enough money to keep its existing system going, Bhatt says, much less remedy a long list of pricey problems. So what exactly is the deficit? To address all statewide transportation infrastructure needs, CDOT says it would require approximately $25 billion.

Coloradans themselves are chiefly to blame for the funding shortfall. The state’s residents voted for the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights in 1992, a constitutional amendment that hamstrings government spending on infrastructure; they tend to loathe tolls; and they haven’t voted to raise the state’s gas tax in more than 25 years. A majority of states tax their gas at rates higher than Colorado. (About 22 percent of CDOT’s budget comes from the state’s gas tax.) Next-door neighbor Utah has raised it twice in the past two decades—all for transportation—and Bhatt notes that the most recent hike was last year. Additionally, Utah siphons a portion of its sales tax revenues to fund highway projects.

When I ask Utah Department of Transportation executive director Carlos Braceras what he’s doing with all that extra money, he says part of the plan is to attract skiers and snowboarders who might otherwise head for Colorado to the Beehive State by making it painless to reach resorts in Big Cottonwood and Little Cottonwood canyons via roomy freeways and new bus routes. Braceras likes to advertise that anyone traveling from Salt Lake City to Park City Mountain, which Vail Resorts purchased in 2014, will enjoy a six-lane interstate—plus passing lanes on the inclines. Braceras also references the snarky billboards that have, at one time or another, popped up along I-70 telling people they could be skiing instead of driving.

Although his state is politically red—a place where voters would typically reject big government spending—infrastructure has been treated differently. “Good roads cost less,” Braceras says. “If you can keep them in good condition, you’re passing on less liability to future generations—and that’s Utah’s principle behind funding transportation adequately.” Braceras and Utah’s Republican governor, Gary R. Herbert, have teamed up to successfully pitch this philosophy to state legislators, who have consistently supported transportation funding. That is not the case in Colorado. Braceras sympathizes with Bhatt, saying, “Shailen is in a very difficult position.”

That’s an understatement, especially with regard to the functionally obsolete I-70. To wit: During the three 2016 winter holidays—Christmas week and Presidents Day and Martin Luther King Jr. Day weekends—the combined number of vehicles on the mountain corridor was 605,518, just slightly less than the entire population of the city of Denver. (The Eisenhower Tunnel set a record in July 2016 when 153,503 drivers made their way through during a single weekend.) “It’s a system that was designed in the ’50s and built in the ’60s for a population that they thought would be about three million statewide in the ’80s,” Bhatt says.

There are now about 5.5 million people living in Colorado, and the population increased by 1.68 percent from 2015 to 2016, according to a 2016 United States census, which makes it the seventh-fastest-growing state in the country (Utah is first). “I probably ski six to 10 weekends a year, and I have raged in this traffic,” confesses Bhatt, who is betting, in part, on technology—including a new CDOT partnership with Panasonic aimed at creating the nation’s first smart highway—to alleviate some of the snarls. But his boss concedes that with so little tax revenue, a comprehensive solution isn’t imminent. (Smart highways will incorporate technology to help monitor road conditions, mitigate traffic, and work in concert with autonomous vehicles, among other things.) “Everybody is always talking about, Why can’t we have nice things like Utah?—wider highways, light rail, and more transit options—but they don’t want to pay for any of those things,” Hickenlooper says. “To play with our competitors, we probably are going to have to raise our taxes a little bit. It’s political suicide to say so—but of course, I’m not running for re-election.”

About an hour into our drive, Bhatt pulls off I-70 into a CDOT staff parking area at the east portal of the Eisenhower Tunnel. He stops abruptly, churning up dust that startles a worker, who grumbles at us, not realizing it’s his superior in the offending vehicle. Looking at the tunnels before us and the lanes of asphalt behind us, Bhatt says, “It’s ridiculous that with all the tourism dollars generated by outdoor recreation, the artery that feeds them is in its original configuration.”

He’s referring to I-70’s four-lane design. Except for added lanes along two short stretches—one near C-470, the other east of Silverthorne—the highway has remained nearly unchanged for roughly half a century. There have only been two major modifications: widening the 900-foot-long Veterans Memorial Tunnels (formerly called the Twin Tunnels) at Idaho Springs, a project that was completed in 2015, and then shortly thereafter converting 13 miles of eastbound shoulder into the new I-70 Mountain Express Lane. With the propensity to become the nation’s highest-priced toll road (it uses a congestion-based pricing scheme that’s generally no more than $5 but has a hypothetical max of $30), it has cut about 15 to 30 minutes from the average weekend commute. “I couldn’t be prouder of that project,” says Bhatt’s predecessor, Hunt, who was a strong advocate for the shoulder-lane toll. “It takes the edge off, but it’s a short-term solution.”

Why it took approximately 50 years to make any meaningful improvements to the interstate’s capacity was not solely a result of funding deficits. First, traffic didn’t become a material factor until the mid-1990s, when Denver’s population began steadily climbing after having flatlined for the previous 25 years. Second, and more consequential, local communities—from Silver Plume to Georgetown to Idaho Springs—were constantly disagreeing about how to move forward once it became clear the highway’s size was insufficient. “All the parties up and down the corridor were battling,” says Steve Coffin with GBSM, a strategic communications consulting firm that represents Clear Creek County. Many of those who live in Clear Creek believed that a six-lane interstate would negatively impact the county. If the government exercised eminent domain to expand the highway, it could wreak havoc on the downtown business corridor in Idaho Springs and irreparably harm some of the smaller towns, like Silver Plume and Georgetown.

Their concerns weren’t just speculation; I-70 had been a community killer in the past. When the highway was originally constructed, 80 historic buildings in Clear Creek County were lost, and Silver Plume was robbed of 20 percent of its land. Idaho Springs and Dumont were similarly affected. “The problem we can’t change is that the highway doesn’t belong where it is,” says Cynthia Neely, the former executive director of the Georgetown Trust for Conservation and Preservation. So in 1989, when CDOT first proposed a six-lane, flattop freeway barreling through the county, Neely and other Clear Creek County residents were naturally resistant. Much of the interstate between Silver Plume and Idaho Springs is already wedged into a narrow valley, obscuring scenic Clear Creek, amplifying the din of traffic, and concentrating pollution. “We live with the congestion and a horrendous amount of noise,” Neely says. “In the summer, you can’t carry on a conversation on my patio when trucks go by.”

In 2004, CDOT and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) announced their intention to conduct an environmental impact study to ensure that future highway development in the mountain corridor met with National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) provisions, requirements the highway did not have to contend with when it was originally built. (Today, NEPA rules would mean building a much more expensive roadway, possibly modeled after the elevated portion of I-70 that cuts through Glenwood Canyon. It’s this type of low-impact design that Neely and Clear Creek County residents have longed for—but will likely never see.) But the local communities, who felt they’d long been excluded from the process, “went on the offensive,” says Tim Mauck, one of three Clear Creek County commissioners. CDOT staff held town hall meetings in corridor communities to present the proposed FHWA study. “County commissioners in Clear Creek, Summit, and Eagle counties worked together to oppose it, submitting public comments and arranging PowerPoint presentations that identified glaring [NEPA] problems,” Mauck recounts in a recent email. “I attended a couple of the meetings and recall the public being pretty hostile.”

Former CDOT executive director Russell George, who came in a few years after the environmental impact study debacle and served until 2011, was determined to break the I-70 deadlock during his tenure. After taking over the directorship in 2007, George formed a coalition called the Collaborative Effort. It comprised 27 different stakeholders, including representatives from city and county governments, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the FHWA, environmental groups like the Sierra Club, and private interests, such as Vail Resorts and Colorado Ski Country USA.

George figured if he could get the various parties to hash out their concerns in person, a plan for how to finally move the mountain corridor forward would emerge. Despite three separate requests, George declined to be interviewed for this story. But Coffin, who was involved in the process, recalls, “Russ told them to stop bickering and arguing and that if they could come up with a consensus approach for the corridor, CDOT would back it. He put the ball in their court.”

The bottom-up strategy worked, and by early 2011 members of the Collaborative Effort had mapped out a detailed framework—which included an environmental impact study that took the communities’ concerns into account—for expanding I-70 through 2050. In June of the same year, the FHWA signed off on the plan, which became known as the Record of Decision, or ROD. It was historic: “It provided a road map that all corridor stakeholders could agree on,” Mauck says. “Rather than being held up in lawsuits [i.e., mountain towns suing the state and/or CDOT], it enabled CDOT to move into construction, saving a tremendous amount of time and money.”

Although many Coloradans may not have heard of the ROD, it is a momentous document—a comprehensive blueprint to make mountain travel on I-70 easy and, dare we say, even enjoyable. The ROD gave CDOT the go-ahead to begin some projects—funded mostly through the department’s regular budget as well as through other CDOT programs and partnerships—immediately. The Veterans Memorial Tunnels were first; then came the Mountain Express shoulder toll lane.

The ROD also sanctioned other improvements, such as a new bore at the Eisenhower Tunnel; upgrades to 26 interchanges; special lanes for slow-climbing trucks; more pullouts, parking, and chain-up stations; a high-speed train that levitates on magnets; more buses, vans, and shuttles; an infusion of new technologies to better inform drivers when road and traffic conditions deteriorate; and ample police to make sure everyone is playing nicely. There’s just one enormous problem: The ROD didn’t provide a way to pay for any of it.

As we head farther west, Bhatt spots a cyclist pedaling furiously along the interstate’s eastbound shoulder. “That’s illegal!” he declares, and while keeping his eyes on the road, he yanks out his iPhone and speed-dials CDOT operations, alerting them to the biker. “Here in Colorado, people see the need for transportation infrastructure investment,” says Bhatt, resuming our grim conversation about funding. “It’s the how that gets very contentious.”

A few weeks earlier, I had spoken with Margaret Bowes, director of the I-70 Coalition, a nonprofit advocate for local governments and businesses along the mountain corridor, who explained that the contention isn’t about anything except money—or, more specifically, the lack thereof. She also said we can’t depend on federal dollars alone to resolve things. Colorado gets about $560 million in yearly appropriations from the FHWA. That’s a start, but it’s nowhere near enough cash to break ground on the multibillion-dollar improvements outlined in the ROD. “I-70 is the lifeblood of Colorado’s tourism industry,” Bowes says. “But it’s only one of many corridors nationwide that needs investment.”

Hickenlooper knows acutely that I-70 requires serious, immediate attention, but he wants some kind of guaranteed state-generated revenue stream to ensure CDOT can finish whatever projects it starts. While gas taxes are an obvious source, they’re also a diminishing one. Automobiles are more fuel-efficient than ever, averaging about 34.2 miles per gallon as of 2014. Plus, some estimates say almost 35 percent of new car sales globally will be electric or hybrid by 2040. That’s much less gas consumption overall, a trend that undermines the effectiveness of a tax. (Utah gets around this in part because its gas tax is variable, indexed to inflation; the state also diverts the revenues it earns from taxing automobile sales and services to transportation spending.)

Joe Mahoney, who works in CDOT’s Office of Major Project Development, has the unenviable responsibility of trying to figure out how to finance transportation projects in penny-pinching Colorado. He concurs with the notion that the gas tax is not a viable long-term revenue source and will become increasingly obsolete. Instead, Mahoney supports tolling because it’s something that can be implemented immediately. “We need money that can be put to use starting next year, not six years from now,” he says. “The policies for tolling are already in place, and they have been for years.”

Still, federal regulations on tolling an existing interstate are complex. There is a flexible provision in FHWA rules, however, that lets states toll noninterstate highways and interstate bridges and tunnels to cover the future costs of upgrading those structures. One of the ways to increase much-needed revenue in Colorado would be to set up tolling stations at the Eisenhower Tunnel, which had 11.7 million vehicles steer through its passageways in 2015. That sounds impressive until you do the math, which, for a typical toll of $4 a pop, generates only $46.8 million annually, leaving the state a couple of billion dollars short. CDOT doesn’t have to have all the money in the bank before it commences digging a new Eisenhower bore, estimated to take at least five years, but it must have a mechanism in place that replenishes its ledgers with enough money to pay for day-to-day construction costs. For tolling to generate that kind of cash—on average, about $1 billion annually—CDOT would have to use variable rates that crank up during peak periods, a so-called congestion charge. Head up skiing on Saturday morning and you’ll pay dearly.

“One way you could get a third bore built is by tolling the existing tunnel,” Bhatt says. “But politically, that’s going to be a challenge.” Hickenlooper could decide to toll the tunnel, but an incoming governor—who might consider campaigning on a promise to repeal the toll—would deal with the repercussions. “There is no magic bullet,” Hickenlooper says. “The solution is going to be in a number of things, all done in concert.”

On July 1, 2015, Oregon instituted the country’s first road-usage charge, an innovative revenue-generating tool also sometimes called a VMT (vehicle-miles traveled) fee. The concept is to charge drivers in the same manner utility companies bill households for electricity: You pay for consumption. A matchbox-size GPS-enabled device plugged into your vehicle’s on-board diagnostic system tracks miles; then you get billed monthly. Oregon has enrolled 1,000 drivers in its voluntary VMT pilot program. “Historically, [VMTs] have been very unpopular with drivers for a variety of different reasons,” Hickenlooper says. “Some people are very concerned about privacy—they don’t want Big Brother to know exactly where they are driving. Some people are concerned that anytime they go anywhere, they’re costing themselves money. But I like them as a philosophical framework because somebody’s got to pay. And if there is a resistance to making the investment, it seems to make more sense to charge the most money to those people who are getting the greatest benefit.”

Hickenlooper realizes it’s not going to be easy to get Coloradans onboard with new tolls, gas taxes, and/or VMT fees. “The way you get something like this funded is by having people believe that the new revenues will really make a difference in their lives,” the governor says. For this reason, Hickenlooper once again looks to our neighbor to the west. The governor is a big fan of Envision Utah, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group that organized several workshops in the late 1990s that brought together Utah residents, business leaders, developers, elected officials, and others to discuss growing their transportation infrastructure—and, just as important, how to pay for it. “They went all over and made sure they got everybody into these town hall meetings—Republicans, Democrats, liberals, conservatives—and had them really haggle and get down into the weeds,” he says. “What came out is a plan that pretty much everybody—every mayor, every county commissioner—had signed off on.”

Hickenlooper wants to do the same thing in Colorado. “It would be a statewide conversation about how we are going to deal with transportation infrastructure in our future,” he says. Although Hickenlooper has already met with two potential funders for the program, it’s uncertain whether he can get the money or momentum required to make it happen before his term ends next year. Until then, he’s going to have to listen to Bhatt’s nagging. “Shailen keeps pointing out these things that are very irritating,” Hickenlooper says. “Things that we should have fixed long ago—and haven’t.”

I’ve been driving with Bhatt for almost two hours when we round Dead Man’s Curve, located at the end of the steep, seven-mile descent into Morrison. Hundreds of crashes, some of them fatal, have occurred here since the highway was built. If this section of road were being constructed today, engineers would never combine such a sharp bend with a precipitous grade. In 1990, CDOT erected several bright yellow signs with warnings like “Truckers, don’t be fooled: 4 more miles of steep grades and sharp curves.” The signage helped, and CDOT has outlined design improvements to further safen this section of highway—but dollar signs are getting in the way of preventing collisions.

When pileups do occur, Bhatt wants drivers to know immediately. Currently, that information comes almost exclusively from technologies that require drivers to take their eyes off the road while careening down overcrowded interstates: CDOT’s Twitter feed and text alerts, its website (cotrip.org), and its 21 variable message boards. (Not to mention third-party, crowd-sourced apps such as Waze.) Eventually, however, Bhatt imagines a world of self-driving cars, connected and communicating over a wireless transportation network—a bona fide information superhighway.

That may sound like a fantasy, but it’s one Bhatt willingly entertains—and with good reason. CDOT research shows that by 2025, even a six-lane I-70 won’t have enough capacity to keep traffic flowing during peak periods. More public transportation is needed—an armada of regional buses that depart from Park-n-Rides on weekends and perhaps a high-speed mag-lev train from Union Station to many of the mountain resorts (CDOT says feasibility studies show the train would never pay for itself)—but it likely won’t be enough on its own. Bhatt knows this, which is why he’s banking on technology to relieve some of the traffic—and to do so for much less money than massive construction projects.

“Widening roads all the time is just a 20th-century mindset,” Bhatt told the Denver Post in January 2015, shortly after accepting the executive director position. To provide an example of how technology—not more asphalt—might be implemented to alleviate congestion, Bhatt points to a new vehicle-to-vehicle data protocol called dedicated short-range communications, or DSRC. “Normally, I have to keep a safe distance from the person in front of me,” Bhatt explains. But, in theory, self-driving autos equipped with DSRC could drive 70 mph with just inches between them. Should the car in front tap its brakes, the DSRC technology would transmit this action in a fraction of a second to the trailing vehicle, which would respond by automatically slowing down to avoid a collision. Bhatt says the elimination of those gaps—the prevailing three-second rule—could more than triple the capacity of a roadway.

In early December, the National High-way Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), part of the U.S. Department of Transportation, announced a proposed federal mandate that would require automobile manufacturers to install DSRC systems in all new cars. The NHTSA solicited public comments on the proposal until the end of January; a multiyear phase-in period was scheduled to begin shortly thereafter. While it may take a decade before all new vehicles are equipped, Bhatt wants CDOT to be ready, so he launched a new program called RoadX in 2015.

I spoke with RoadX director Peter Kozinski in November, a few days after Panasonic had announced its new partnership with CDOT to create the nation’s first smart highway—or “integrated connected vehicle platform,” in industry jargon—on the mountain corridor. Panasonic will work with CDOT to convert an ordinary blacktop interstate into a sophisticated communications network. The basic idea is to collect and disseminate data from multiple sources, including embedded pavement sensors and roadside weather towers (many of both are already in place) that can detect things like rain and snow. Meanwhile, DSRC-equipped vehicles can dispatch their speeds, locations, and other useful tidbits, like whether their drivers are slamming on the brakes. All this intelligence will get fed into a cloud computing platform “where it will be ingested, analyzed, evaluated, cleansed, and returned in a very rapid time frame,” Kozinski says. And by “rapid,” he means within a matter of seconds.

The upshot is that 15 or 20 years from now, the majority of SUVs, campers, police cars, snowplows, trucks, ambulances—you name it—will be in constant communication with every other vehicle, with CDOT, and even with the roadway itself. Anyone driving from C-470 to Glenwood Springs will be alerted immediately when there is an accident or road closure, or her self-driving car will reduce its speed because the network notified it to an upcoming patch of black ice. It’s likely Panasonic will be supplying much of the hardware and software at a heavily discounted cost as well as kicking in other significant resources (CDOT is committing $7.5 million). “It could be the national model for how vehicles, infrastructure, and systems all talk to one another,” Kozinski says.

Later this year, CDOT will outfit 500 vehicles in its fleet (and potentially the same number of private cars) with DSRC devices to act as “probes”—part of a test to determine how to collect and disseminate data. The agency also launched a pilot program this winter, enlisting 1,000 frequent mountain corridor drivers to evaluate a system that promptly delivers traffic info to smartphones over existing cellular networks—a measure that will complement DSRC once it becomes less of a fantasy and more of a reality.

Before heading back to CDOT’s headquarters in downtown Denver, Bhatt swings by the agency’s Traffic Management Center in Golden and invites me inside. Staffers at computer terminals are monitoring highways around the state, primarily by watching a wall-to-wall video projection that displays live feeds from roadside cameras. Today, when an accident occurs, the information is conveyed manually: Traffic managers compose warnings for physical message boards, send texts and tweets, update CDOT’s travel website and 511 information line, and alert emergency personnel. Eventually, says Bhatt, the facility in Golden (along with a similar center located above the Eisenhower Tunnel) will share data with drivers automatically.

“If an RV ahead of me blows a tire, that vehicle would start broadcasting that it’s stopped,” Bhatt says. CDOT would receive that information and then transmit it to vehicles on the affected roadway. At this point, hypothetically, your self-driving car would quickly change lanes to avoid rear-ending the disabled RV. Or if you’re a few miles back, it would preemptively reroute you—and everyone else—onto a frontage road to help thwart a major backup.

Bhatt’s vision is compelling. But CDOT’s track record for leveraging technology isn’t exactly stellar. I’m a regular I-70 traveler and can confirm, at least anecdotally, that CDOT’s existing systems aren’t consistently reliable. The agency’s 511 line is an analog holdover with time-lagged reports offering limited usefulness, and CDOT currently doesn’t have a functioning smartphone app.

The overhead signboards along the mountain corridor aren’t always effective, either. On I-70 in Vail, I’ve seen them displaying two-hour drive-time estimates to Denver only to discover the interstate is closed a few miles ahead. While heading home from skiing with my family recently, the signboard message at Empire Junction read, “Heavy traffic. Slower speeds to Idaho Springs.” But we did 65 mph to Idaho Springs, where we stopped for dinner. An hour later, the warning remained despite zero congestion—an avoidable hiccup that caused precautionary braking because drivers were expecting to come to a screeching halt at any moment.

When I ask Amy Ford, director of communications for CDOT, about this, she tells me that operators working in the control center at the Eisenhower Tunnel update the signs every 30 to 60 minutes. “[They] are also doing a variety of other tasks, including maintenance, dispatch, emergency response, and running the express lanes.” That’s fair, but one has to wonder how CDOT could possibly be trusted to deliver real-time data to my car so I can safely drive three inches from the guy in front of me if the agency cannot even refresh its freeway message boards more than once or twice an hour.

Then again, with its laughably small budget, CDOT’s ability to keep its road system operating is nothing short of a miracle. Even during major blizzards, its plows somehow get the major highways cleaned up in a few hours, with rare exceptions. And lately, the agency has been working with tow-truck drivers to halve the time it takes to clear wrecks. Even with those minor wins, CDOT’s top brass rarely get to relax. Hunt explains it this way: “My wife and I would read tweets on CDOT’s traffic-information website over the weekend as we sat and watched how I-70 was operating, living in fear I was going to get a phone call at any minute on a Sunday afternoon.”

When Hunt was at CDOT’s helm, he occasionally spoke with Bhatt to talk shop because they shared a common philosophy: that interstates are catalysts for a state’s economic growth and prosperity. “The Denver metro area stays competitive in the country because of what we have to offer—access to incredible outdoor recreation,” Hunt says. To ensure that access remains, he says, “you need to make the mountain corridor a priority, and you have to be creative to make the situation better.” But Hunt and Bhatt, and Hickenlooper too, will tell you that it’s imprudent to add capacity to I-70 without also addressing critical shortcomings elsewhere in the state. And there are plenty—Colorado’s road system ranks among the 10 worst in the United States.

All this is to say that it may be a while before the mountain corridor gets the attention it so desperately needs—and we all so desperately want but haven’t been willing to pay for. Which, Bhatt says, makes it critical to implement programs like RoadX as soon as possible. Until then, I’m abandoning modern technology and going old-school. I carry a VHF radio in my SUV to eavesdrop on highway chatter between local and state police and CDOT snowplows in the winter. It’s remarkably handy because I learn about I-70 closures and accidents the instant they occur. The tactic impresses Bhatt, who says to me, only half-jokingly, “You’re like the road whisperer.”

Copyright © Michael Behar. All Rights Reserved.