“I Told Them It Was a Terrible Idea” Download PDF

“I Told Them It Was a Terrible Idea” Download PDF

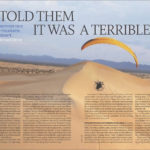

A paramotor race over mountains and desert

Trey German got a late start on the day he crash-landed into a cactus field and ended up with dozens of inch-long spines protruding from his butt. German, 30, lives in Houston, Texas, and is a paramotor pilot. His encounter with the cactus occurred while he was competing in the Icarus Trophy, a 1,000-mile air race that spans five Western states. From its start in Polson, Montana, near Glacier National Park, German had been following the race route south. He’d threaded the Rocky Mountains into Idaho and was midway through Utah’s desert badlands when what might be considered a piloting error forced him to descend.

A U.K.-based outfit called the Adventurists organizes the Icarus Trophy, along with several other madcap exploits, including a 1,800-mile rickshaw run through India and a sidecar-motorcycle rally across Siberia’s frozen Lake Baikal. This month, the Adventurists will host their third annual Icarus Trophy, charging entrants $2,200 to participate. German plans on entering again. Last year he and six other pilots took flight on a cloudless, crisp October morning from a grassy median at the Polson Airport, on the southern shore of Montana’s Flathead Lake. Seven days later, German had covered more than 600 miles when he arrived in Moab, Utah, where he spent the night sleeping in the driver’s seat of his jeep, which his ground-support crew had been using as a chase vehicle.

Paramotorers prefer to fly very early in the morning, while the air is still. As the day progresses, heat from sunlight forms thermals—updrafts that can be violent and make it impossible to fly in a straight line. The morning after he arrived in Moab, German had intended to be airborne by dawn. But “technical problems,” he says, delayed his departure until 11 a.m. (When I push for specific, he admits sheepishly that “everyone had enjoyed themselves” a bit too much the prior evening.)

“By the time we launched, the winds were picking up and the air was super bumpy,” he tells me. The midday thermals tossed him around like a wiffle ball in a wind tunnel. His altimeter indicated precipitous ascents and descents—ups and downs of 1,000 feet per minute. “It felt like I was free-falling or like a parachute had just opened and jerked me upward,” he says. German was hoping to make it to Monticello, Utah, about 60 miles due south of Moab, where he planned to refuel his five-gallon tank. But as he approached the town, gusty winds smacked headlong into his glider. “My progress slowed to almost a standstill,” German recalls. “I think I was doing about five knots, tops.”

Next came the sickening sound no paramotor pilot ever wants to hear: a staccato sputter from his engine, then silence. “I knew I was out of gas and that I’d have to land in a field, so I started scoping out my options.” Moments before touching down, he realized a robust tailwind was impelling him way too fast to land on his feet. If he tried to run off the excess speed, he’d almost certainly snap an ankle or get dragged onto his face. So he made a quick decision to raise his legs and plop onto his butt. “It was around this time I started to notice some pain in my hindquarters,” German says. He had skidded 30 feet, colliding with numerous low-lying cacti.

IN PARAMOTORING, OR POWERED PARAGLIDING, as it’s also called, the pilot wears an aluminum-framed backpack outfitted with a two-stroke piston engine, similar to what’s in a lawn- mower. Cranking out between 20 to 30 horsepower, it drives a two- or three-blade propeller (often made of carbon fiber) to produce thrust. A banana-shaped “wing” is fashioned from rip- stop fabric, a durable and near-tear-proof nylon. Lines connect the wing to a body harness worn by the pilot. To take off, the pilot revs the engine while running; the forward motion forces air into vents along the wing’s leading edge, filling hollow chambers, called cells, sewn into the canopy. Eventually, the wing “inflates,” forming itself into a conventional airfoil that generates lift.

Paramotoring evolved from paragliding, which emerged in the 1970s when a handful of daring climbers in the French Alps decided to employ parachutes to expedite their descents from peaks they’d summited. But the existing parachutes were awful gliders: For every three feet of forward progress, they’d plunge one foot lower. The switch to non-porous fabrics, longer wingspans, and different airfoil shapes led to the modern-day paraglider wing. Pilots can now achieve up to 11:1 glide ratios with wings so efficient they can harness rising heat to soar on thermals for hours. It’s also possible to travel great distances: The world record is 350 miles, covered in a single 11-hour flight.

But to launch a paraglider you either have to hike or drive to a very high point, like a mountaintop or, if you’re a flatlander, rely on a ground-based winch-and-cable mechanism (usually n a truck or boat) to tow you to a suitable altitude and then release you. In 1980, Mike Byrne, a Brit from Essex, England, constructed what is thought to be the first paramotor and coined the term. It was a homebuilt rig, which he used to power a paraglider wing and make several flights in the U.K. Not long after, the French aerospace company La Mouette began manufacturing and selling paramotors, and the sport swiftly gained momentum. Pilots could take off and land just about anywhere; no longer did they have to lug gear long distances to reach elevated launch points or use tow systems.

I get a firsthand look at paramotoring in June, when I join Mike Bennett near Watkins, Colorado, about 25 miles east of Denver. We’re at a derelict dirt airstrip formerly used by fixed-wing ultralights, popular in the late 1970s and early 1980s because they offered an inexpensive and largely unregulated entrée into powered flight, the same reason many now take up paramotoring. The paramotor itself is remarkably compact. Bennett’s engine and prop sit inside a mesh cage that’s about four feet wide and hemispheric in shape, like an oversized wok. It would t easily into the trunk of a typical four-door sedan.

Watkins is having a spell of hot weather, with temperatures nearing 100 degrees. So I agree to meet Bennett at 6 a.m., shortly after sunrise, to beat the heat and the turbulent air that comes with it. He wants to compete in the Icarus Trophy race in September. “But I just got a new job,” he bemoans. “I’m not sure yet if I can take the time off.” Even so, Bennett has been training, doing longer-than-usual “cross-country” flights from Watkins to Colorado Springs, about 80 miles one way. (Most paramotorers fly exclusively at their “home field” and almost never venture into hilly or mountainous terrain. “The winds in the mountains can cause a lot of turbulence and you can have a wing collapse,” says German.)

I watch Bennett carefully lay out his wing, fluffing it up like a down pillow until it stands upright along its trailing edge. “We call this ‘building a wall,’” he explains. Next he walks out the lines attached to the wing, letting them slip loosely through his fingers to feel for tangles or twists. With the paramotor now strapped to his back, Bennett pulls the starter rope and the engine screams to life. Despite a muffler affixed to the exhaust pipe, it’s painfully loud, so Bennett wears noise-canceling earmuffs. A quick snap on the lines brings his wing overhead. He takes a succession of elongated leaps, and moments later sails gracefully into Colorado’s cerulean sky.

Bennett buzzes near the ground, sometimes skimming inches above the native buffalo grass and pink-fringed primrose that conceal what was likely a bustling airstrip during the ultralight heyday. Other times he climbs to 500 feet—his engine generating 150 pounds of thrust—and performs wingovers, spiral dives, and barrel rolls (called “acro” maneuvers in paramotor lingo). After about 15 minutes, Bennett cuts the engine and oats to a gentle stop—known as a “spot landing”—a mere five feet from where he parked his Ford SUV. Other paramotor pilots had told me they often drop into roadside gas stations to refuel, a degree of precision that seemed preposterous until I witnessed Bennett stick his landing in three steps. “I used to do high-power model rocketry and got into paramotoring so I could find my lost rockets,” he tells me. “But I loved it so much, I sold all my rockets and this is all I do now.”

I begin to understand the addiction when Bennett gives me a turn, sans motor, teaching me the art of “kiting”: the basics of flying the wing from the ground. He shows me how to point myself properly into the wind for takeoff. There is a barely noticeable breeze, perhaps three or four knots, but it’s enough, Bennett assures me. On my third attempt, I finally coax the wing into the air and manage to keep it centered above me in a precarious hover. “Run, run, run!” shouts Bennett, who is also an instructor, certified by the United States Powered Paragliding Association. As I start to sprint, the lines I’m gripping become taut, at which point I release them, as Bennett had instructed, letting the body harness take over. Bennett chases after me. When he catches up, he shoves his palms into my lower back, pushing me increasingly faster to generate more lift from the wing. Suddenly, I’m on my tiptoes and then for a few exhilarating seconds my feet actually leave the ground— and I’m flying.

THE ADVENTURISTS’ FOUNDER, Tom Morgan, has a buddy who runs a company based in Dorset, England, called Parajet International, which designs and sells paramotors. Three years ago, that friend offered to teach Morgan how to paramotor. “He gave me 20 minutes of instruction and then I had a go at it,” Morgan tells me. “I immediately regretted it because I soiled myself taking off into the sky without having any idea of how to come down.” Morgan eventually plowed belly-first into a field. Despite some scrapes and bruises, he relished the thrill, and summarily decided to include a cross-country paramotor competition in the Adventurist lineup. “The fact that they can go anywhere, you can land anywhere, you can refill on ordinary fuel from a petrol station made them perfect for long-distance adventures. I just couldn’t believe it hadn’t already been done.”

“There’s a reason it hadn’t been done,” explains paramotorer Shane Denherder. “Because it’s really dangerous, especially taking new guys to do cross-country unsupported flying and racing.” To plan the Icarus Trophy, the Adventurists hired Denherder, a former Blackhawk helicopter pilot for the U.S. Army who served three tours in Iraq planning air assault missions and carried out chopper rescues in Louisiana during Hurricane Katrina. “I was the first person they contacted who was level-headed, and I told them it was a terrible idea,” Denherder says. But Morgan was insistent. “Tom does these crazy adventure races and thought it would be a really good thing to include paramotoring.”

The sport is regulated under the Federal Aviation Administration’s statute for ultralight aircraft, called Part 103. The rules prescribe, among other things, a maximum speed (55 knots, or 63 mph) and weight (254 pounds, excluding the pilot). Pilots also cannot fly at night or carry more than five gallons of fuel. A pilot’s license is not required. In fact, no technical training of any kind is mandated. In theory, you could buy a paramotor engine and wing on eBay and attempt to fly it without any schooling whatsoever. Doing so would almost certainly kill you. For this reason, Denherder and other paramotor pilots strongly suggest getting training from an instructor affiliated with the U.S. Powered Paragliding Association.

For the Icarus Trophy, Denherder established a safety and support protocol designed to enable any paramotorer to participate, despite his or her experience. Each pilot also carries a two-way hand-held satellite communication and navigation device, which transmits location, altitude, and airspeed data to Denherder and his support crew, who follow from the ground with mobile tracking software. Whenever a pilot takes off or lands, they’re required to send a satellite text to Denherder’s team. If they notice that a pilot’s GPS track has stopped moving for more than five minutes, Denherder will re off a message to make sure he or she is okay. If there were no immediate reply, he’d assume the pilot is in trouble and initiate a rescue. (The entrance fee pays for this support.)

For the truly uninitiated, Denherder created a shepherding program—new for 2017—that will pair an experienced paramotorer with newbies to the sport. Byron Leisek, 38, a two-time Icarus competitor, will help novice pilots through the upcoming race. “Sometimes I’ll fly with them,” Leisek explains. “Other times I’ll be their ground support, making calls on weather and wrangling them up at night for debriefings and motivation to give them extra confidence.” Leisek grew up in a family of hot-air balloonists, and his father bought him a hang glider for his 13th birthday. He made his first solo flight on it shortly thereafter. Now he runs a paramotoring school with Denherder called Team Fly Halo, offering weeklong training camps on the beach in Pacific City, Oregon, and in northern California. “I got into the sport to get away from the busyness of the world,” says Leisek, who packs along a tent and sleeping bag during paramotoring jaunts into Oregon’s Cascade Range. “I can drop into a meadow, spend a night or two, explore, and then hop on my machine and fly out.”

Joining the shepherd group this year will be Jason Lehel, 56, an independent lm producer and director based in Los Angeles. He’s also an avid skydiver. Lehel took up paramotoring in 2015 and later learned about the Icarus Trophy when a friend emailed a link to the race website. “I put it in the back of my mind because I thought it was crazy,” Lehel says. But cross-country flying always appealed to him. “It was why I originally got into powered paragliding.” Last fall, while paramotoring in Monument Valley, on the Utah-Arizona border, Lehel happened to meet Leisek, who was in the area for the Icarus race. “He told me about the idea of him shepherding, and I thought it was ideal for my first real serious cross-country flight. I could do it with a relative amount of safety and wisdom alongside me.”

FOR THE ICARUS TROPHY, pilots can register for “race division,” which requires them to complete the route without help, outside Denherder’s team. “They can only progress by flying or walking,” state the official rules. “If they walk, they must carry their equipment.” The fastest time to the finish wins the trophy and bragging rights. Or they can join the “adventure division,” which allows them to enlist help from ground crews, friends, locals, even Uber drivers if they get stuck somewhere and can’t fly out. There are also two RVs tailing the pilots: one carries food, water, spare parts, and other necessities; a second has a mechanic who is also a paramotor instructor. “If there is somebody who is relatively new and needs help, he’s there for them,” says Denherder.

The adventure division is about smelling the roses. “It’s one big flying party,” says Denherder. That’s probably what Leisek had in mind when he signed up. “My goal was to hit every natural hot spring I could,” he says. “I landed on the front door of three of them, disconnected from my gear, and got into the water. I had the best time of my life.”

David Wainwright, an Australian, won the 2016 Icarus Trophy, completing the 1,088-mile route in six days, one hour, and 52 minutes. But he was so far ahead of the other racers that instead of waiting around, he decided to backtrack and join the adventure division pilots in the air as they meandered leisurely through southern Utah. Leisek did the same thing when he flew in the race class in 2015. “When I got to the end, it was lonely and boring,” he says. “So I turned around and headed back to the adventure crew—that’s where the fun was.”

Paramotoring isn’t without risk. Bennett had an accident without even leaving the ground. After making a carburetor adjustment, his engine unexpectedly throttled up to 8,000 rpm in less than a second. The force threw him on his back and the spinning prop clipped his skull, leaving him with a serious concussion and a wound requiring 60 stitches. The Icarus Trophy elevates the danger quotient because it adds 10,000-foot peaks, remote slot canyons, unforgiving deserts, and the physical and mental exhaustion that comes with flying days on end without respite. Pilots also try to avoid drinking too much water because landing to pee takes extra time and burns fuel. But the strategy can back re. “I got severely dehydrated and was in bad shape,” Leisek recalls of his experience racing in 2015.

As for German’s run-in with cacti, it didn’t prevent him from continuing. Two Icarus pilots who witnessed the accident landed nearby to check on him. “Eventually, I was able to get all the thorns out,” German says. German’s ground crew arrived and the team agreed to take a break for the afternoon. The following morning, he flew south, then doglegged west at Monument Valley, continuing another three days and 300 miles to cross the finish line at a blacktop airstrip in a tumbleweed town called Mesquite, Nevada.

For the 2017 Icarus Trophy, German will compete in the race division. The course, which differs slightly from the adventure route, passes through more scenic territory that German wants to see. (He also wants to be the first American to win the race.) “Last year was a new experience for me: my first cross-country paramotoring flight,” he says. “It was surreal and scary. But I knew I wanted to do it, and push myself, because that’s how the greatest things in life happen.” Before he began paramotoring, German spent three years and $10,000 obtaining his pilot’s license, but he soon lost interest in flying fixed-wing airplanes. “They were more of a hassle and prohibitively expensive. The insurance, maintenance, gas…and then I discovered powered paragliding, a much more pure experience because you are literally out there in the air you’re flying through. You can feel the wind and sun on you, and if you fly through moisture, you feel the coolness on your face.”

Copyright © Michael Behar. All Rights Reserved.